For an image to be, does an agent have to observe and process it?

Computational Images

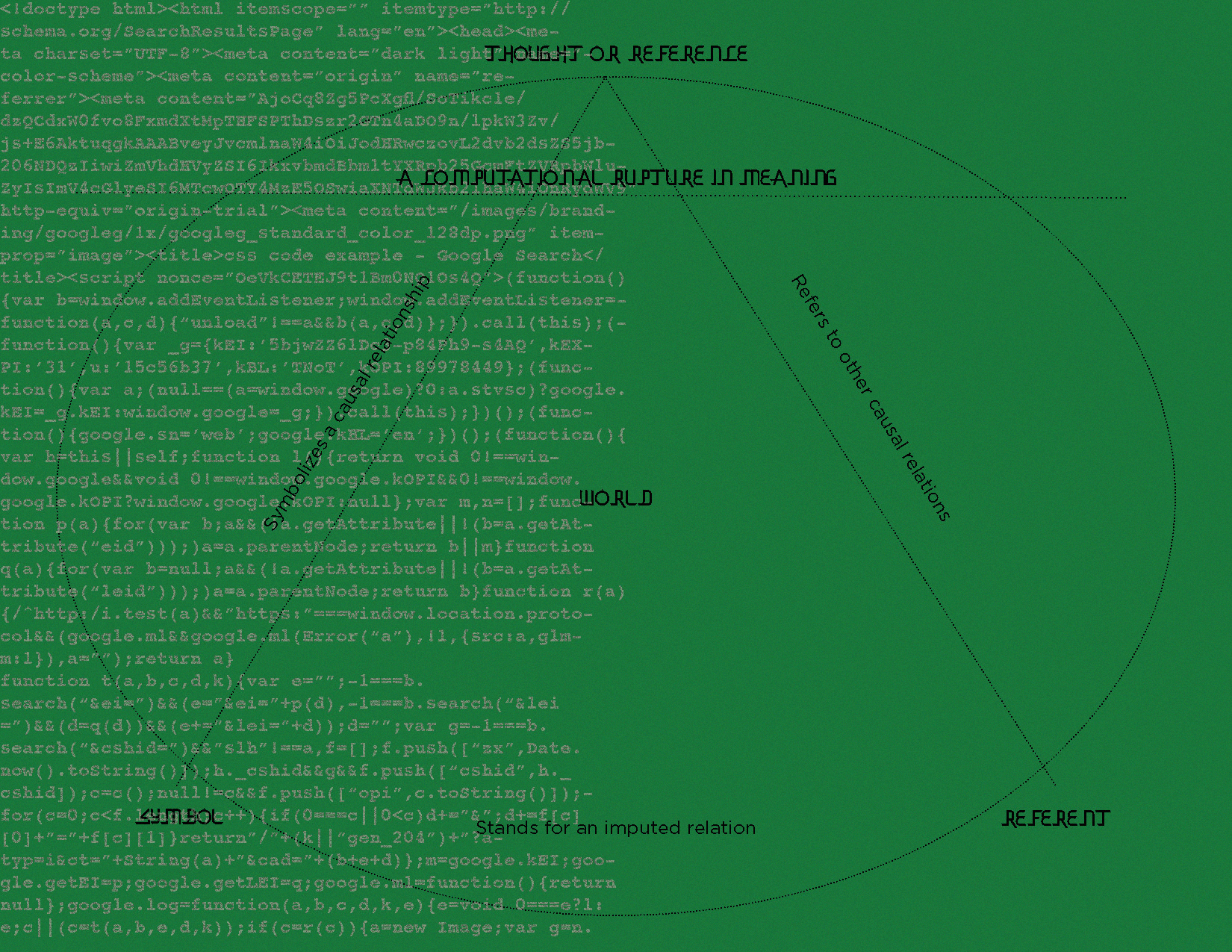

The Specter of Representation

“Everything we see hides

another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see. There is an

interest in that which is hidden and which the visible does not show us. This

interest can take the form of a quite intense feeling, a sort of conflict, one

might say, between the visible that is hidden and the visible that is present.”

René Magritte, interview response to his self-portrait painting Son of Man (1964)

The processes of computation and automation that produce digitized images have displaced the concept of an image once conceived through optical devices such as a photographic plate or a camera mirror that were invented to accommodate the human eye. Computational images exist as information within networks mediated by coded machines. They are increasingly less about what art history understands as representation or photography considers indexing and more an operational product of data processing determined by numerical information. Within this new reality, artificial intelligence (AI) applications are rapidly burgeoning as dominant sources of image production. What becomes of a visual world mediated first by data points from a specific training set expressed through tokens, pixels, text?

In this performative website, an extension of my PhD project, I take images as objects to help me think about the philosophy of computation. My account includes a history that is not intended to be exhaustive in the way a historian might undertake, but rather to serve as a theoretical framework that problematizes the political, social, and epistemic causes and effects of computation on the concepts of representation and truth. In the pursuit of such a multidisciplinary analysis, my approach melds theory with practice to serve as investigation of the past, critique of the present, and radical speculation for futurity. If this approach retains anything from the history of philosophy, it is the spirit of askēsis, an exercise in knowing and becoming myself in the activity of thought. The double bind of critically analyzing representation requires the accounting of oneself in the act, thus the process is always both reflective and self-reflective at the same time. In this context, my analysis takes the form of a neural network, linking ideas, histories, names, and objects in multiple dimensions that can be read in multiple ways. Here, the speculative character of this project is intended to function like a database, affording the reader the chance to draw their own connections and to provoke the forming of new lines for what is possible.

link to dissertation: here

interstices of AI 1, 2023. Video made by interpolating between digital photographs taken by me, using Runway ML’s frame interpolation tool. Track Chahargah I, Op.75 by Ata Ebtekar

What is an image?

Post-Image

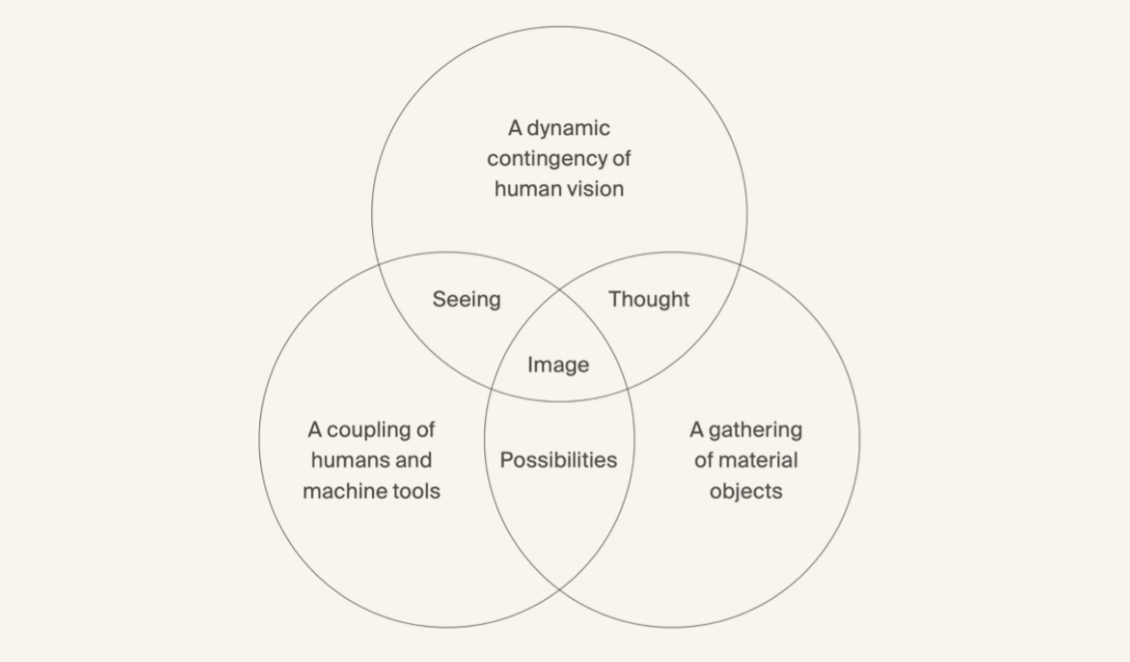

On a specific theory of images, I follow W.J.T Mitchell in distinguishing between picture and image. Where pictures are concrete objects, images are virtual and phenomenal appearances presented to a beholder through objects. “To picture” is a deliberate act of visual representation, whereas “to image or imagine” is more elusory, general, and spontaneous.[1] Pictures–and photographs–can be taken, while images are made. I think about what to make of images that are made today, co-constructed by sets of computational logic that test the limits of human representation.

Representation is insufficient as a concept to explain instances when images are made and distributed between machines with either subperceptual or little to no human intervention. Here, I identify the capacity of art to transfigure (transmogrify, transduce) the illegibility of computation and AI into new pathways for experiencing the world by material investigations that gesture towards the possibilities of difference. The open indeterminacy of computation allows for an opportunity to decenter normative ideas of what is defined and counted as human.

Firmly in an epoch of algorithmic culture, where computational agency, intelligence, and creativity are legitimate ideas to ponder, I also want to think about its history and its politico-epistemic effects on images. If we can fight to make this new world fairer and more available, wrestled away from its racialized techno-capital-military influences, it is a fight worth having for a future whose cosmology we can start creating today. The relinquishing of the primacy of the human eye and the acknowledgment of the failures of human exceptionalism allow us to experience the world in new and deeper ways. Like symbiotes or cyborgs, we have adopted new epistemic instruments that produce entirely new worlds in collaboration with computing intelligence. The computational sublime is a particular concept developed as a potential escape from automated surveillance culture.

At its most insidious, I argue that the complete cognitive offloading of imaging and sight to computation (the statistical gaze) leads to second order social consequences that intensify sensory-overload (chaos or arbitrariness or unknowability) and enable abuses of power. By second order I mean consequences that are not the direct goal of technological development but nevertheless part of its outcomes. Two specific consequences I identify are: 1) the ways in which human correspondence with social reality is obfuscated and homogenized by narrow applications of computation, and 2) how the ubiquity of surveillance as an outgrowth of computation is changing the form of power dynamics.

My unit of analysis follows the development of computation and is thus not reducible to one society or individual, although I focus mostly on its Western origin story and implications. When I consider social relations, I mean the interactions among organisms that live and commune together. Human social relations are increasingly complexified by myriad variables that affect how we communicate, think, exchange, and live. I consider the effects of computation within this broader framework of the social, which for me also encompasses culture.

“Firmly in an epoch of network culture, where computational agency, intelligence, and creativity are legitimate ideas to ponder, I also want to think about its history and its politico-epistemic effects on images.”

My argument implies that computation, as a new form of mediating the world, enables a deluge of opaque image production that challenges how we can know or make sense of things. The human optical system becomes one part of a larger loop of information processing. For example, an analysis estimated that from 2022 to 2023 alone, Artificial Intelligence (AI) was used to produce 15 billion images, a figure that took photography 150 years to reach (circa 1826 until 1975).[2] The argument also implies that beyond simply facilitating this torrent, computation is responsible for the development of visual surveillance tools that enable new ways of monitoring, measuring, predicting, commodifying, and controlling individuals and large groups of people.

Jacques Rancière’s concept of the distribution of the sensible defines politics in a way that includes what Michel Foucault called the order of things, or what is symbolically representable at any given place and time. When combining the two concepts, the struggle over the methods of sensing and the process of perception establishes a relation I call political. The distribution of the sensible contains the ethical, intellectual, and political as aesthetic experiences. The aesthetic here is not about the judgment of beauty but rather the relationship between sense perception, embodiment, meaning, and social relations.

Rather than a critique, my method of analysis is more akin to what Eyal Weizman and Mathew Fuller define as investigative aesthetics. The practice of investigative aesthetics creates observable composites using various signals that include forensic, technical, material, cultural, political, and ethical evidence. Various online and offline methodologies are combined together in transdisciplinary or antidisciplinary work to render the causes of an event or the existence of an object visible.

Practitioners deploy computational methods within legal, forensic, artistic, and critical frameworks. Investigative aesthetics takes seriously the material conditions through which events occur and attempts to create a public alternative to facts presented by power-holding actors. In so doing, it also points to longer historical processes that shape events and outcomes in the present, what I think of as the archaeology of an event. Weizman and Fuller leverage the technical in the spirit of producing a commons for knowledge that resembles a multisensory, navigable architectural model. To experience and make sense of the world and to feel spurred on to imagine it differently are aesthetic experiences and require investigative practices.

“In so doing, it also

points to longer historical processes that shape events and outcomes in the

present, what I think of as the archaeology of an event.”

This method expands the aesthetic and logical limitations of a single human subject, and thus expands a collective’s ability to sense and reason. I loosely follow their concept of investigative aesthetics throughout in attempting to agnostically make sense of computational logics and practices while retaining an ethical commitment to harm reduction and the principle of freedom. My methodology includes producing an archive, constructing a theoretical framework, empirically testing through technical and artistic practices, and relying on transdisciplinary research and pedagogy. The goal of my project is to create an ongoing framework for understanding and creating computational images that is open to new information, new case studies, and new practices (evidence).

[1] Mitchell, W., Representation, in F Lentricchia & T McLaughlin (eds), Critical Terms for Literary Study, 2nd edn, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1995, 4.

[2] Every Pixel Journal

What gazes back?